Charles Darwin and Evolution

By Arnav Choubey

When on board H.M.S. ‘Beagle,’ as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species.

This light, of course, was Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection, encapsulated in these five claims:

(Darwin, 1859)

- Nonconstancy of Species

- Common Ancestry

- Gradual Evolution

- Multiplication of Species

- Natural Selection

Claim #1: The Nonconstancy of Species

We have many slight differences which may be called individual differences, such as are known frequently to appear in the offspring from the same parents, or which may be presumed to have thus arisen, from being frequently observed in the individuals of the same species inhabiting the same confined locality. No one supposes that all the individuals of the same species are cast in the very same mould.

(Darwin, 1859)

Changes in the susceptibility of bacteria can be primary or secondary. Primary resistance arises as a result of a spontaneous mutation and can appear without contact with a drug. This type of resistance is encoded chromosomally and is not transmitted to other bacterial species. The frequency of occurrence of mutated bacteria is low, but in the presence of an antibiotic, mutants have an advantage over the rest of the population, and thus they survive and outnumber susceptible populations. They can spread to other ecological niches in the same individual or can be transferred to other macroorganisms. While defending themselves against antibacterial agents, including antibiotics, in the course of their evolution, bacteria have developed a variety of mechanisms counteracting the effects of antibacterial agents. As a result of the acquisition of resistance genes, bacteria become partly or entirely resistant to a given antibiotic

(Urban-Chmiel et al., 2022)

Claim #2: Descent from a Common Ancestor

Great as the differences are between the breeds of pigeons, I am fully convinced that the common opinion of naturalists is correct, namely, that all have descended from the rock-pigeon (Columba livia)

(Darwin, 1859)

[Universal common ancestry] is now supported by a wealth of evidence from many independent sources, including: (1) the agreement between phylogeny and biogeography; (2) the correspondence between phylogeny and the palaeontological record; (3) the existence of numerous predicted transitional fossils; (4) the hierarchical classification of morphological characteristics; (5) the marked similarities of biological structures with different functions (that is, homologies); and (6) the congruence of morphological and molecular phylogenies.

(Theobald, 2010)

Among a wide range of biological models involving the independent ancestry of major taxonomic groups, the model selection tests are found to overwhelmingly support [universal common ancestry] irrespective of the presence of horizontal gene transfer and symbiotic fusion events. These results provide powerful statistical evidence corroborating the monophyly of all known life

(Theobald, 2010)

Claim #3: Gradual Evolution

We see nothing of these slow changes in progress, until the hand of time has marked the long lapse of ages, and then so imperfect is our view into long past geological ages, that we only see that the forms of life are now different from what they formerly were.

(Darwin, 1859)

It seems pretty clear that organic beings must be exposed during several generations to the new conditions of life to cause any appreciable amount of variation; and that when the organisation has once begun to vary, it generally continues to vary for many generations. No case is on record of a variable being ceasing to be variable under cultivation. Our oldest cultivated plants, such as wheat, still often yield new varieties: our oldest domesticated animals are still capable of rapid improvement or modification.

(Darwin, 1859)

It is known that the English pointer has been greatly changed within the last century, and in this case the change has, it is believed, been chiefly effected by crosses with the fox-hound; but what concerns us is, that the change has been effected unconsciously and gradually, and yet so effectually, that, though the old Spanish pointer certainly came from Spain, Mr. Borrow has not seen, as I am informed by him, any native dog in Spain like our pointer.

(Darwin, 1859)

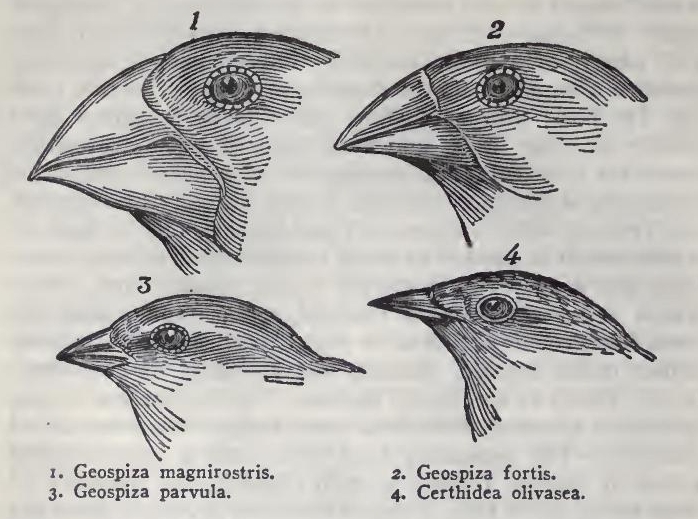

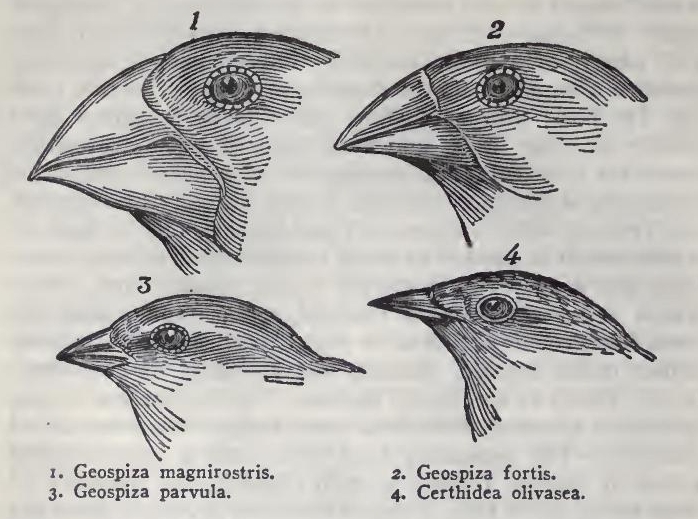

The most curious fact is the perfect gradation in the size of the beaks in the different species of Geospiza, from one as large as that of a hawfinch to that of a chaffinch, and (if Mr. Gould is right in including his sub-group, Certhidea, in the main group) even to that of a warbler. The largest beak in the genus Geospiza is shown in Fig. 1, and the smallest in Fig. 3; but instead of there being only one intermediate species, with a beak of the size shown in Fig. 2, there are no less than six species with insensibly graduated beaks. The beak of the sub-group Certhidea, is shown in Fig. 4. The beak of Cactornis is somewhat like that of a starling, and that of the fourth sub-group, Camarhynchus, is slightly parrot-shaped. Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.

(Darwin, 1839)

Claim #4: The Multiplication of Species

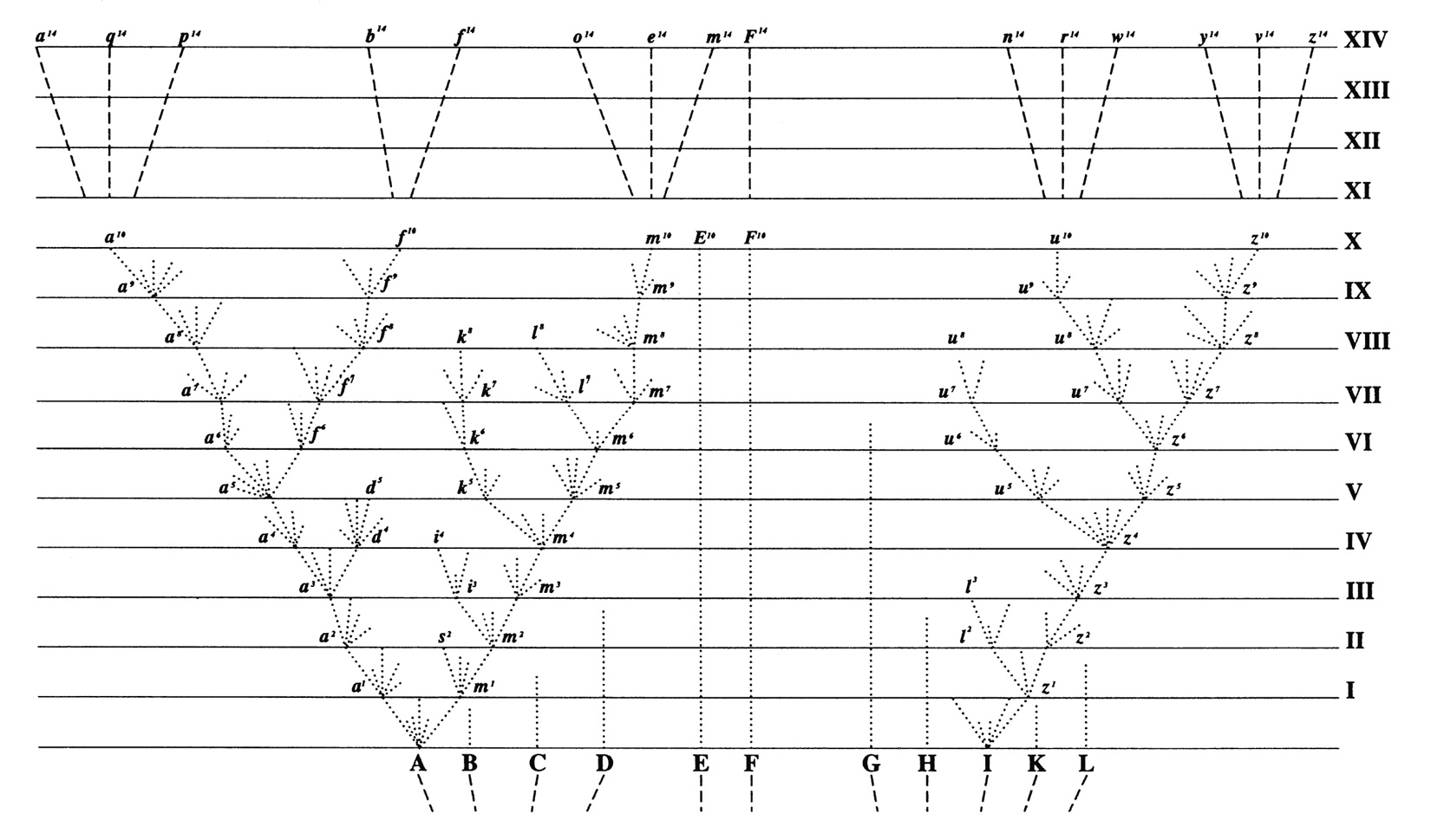

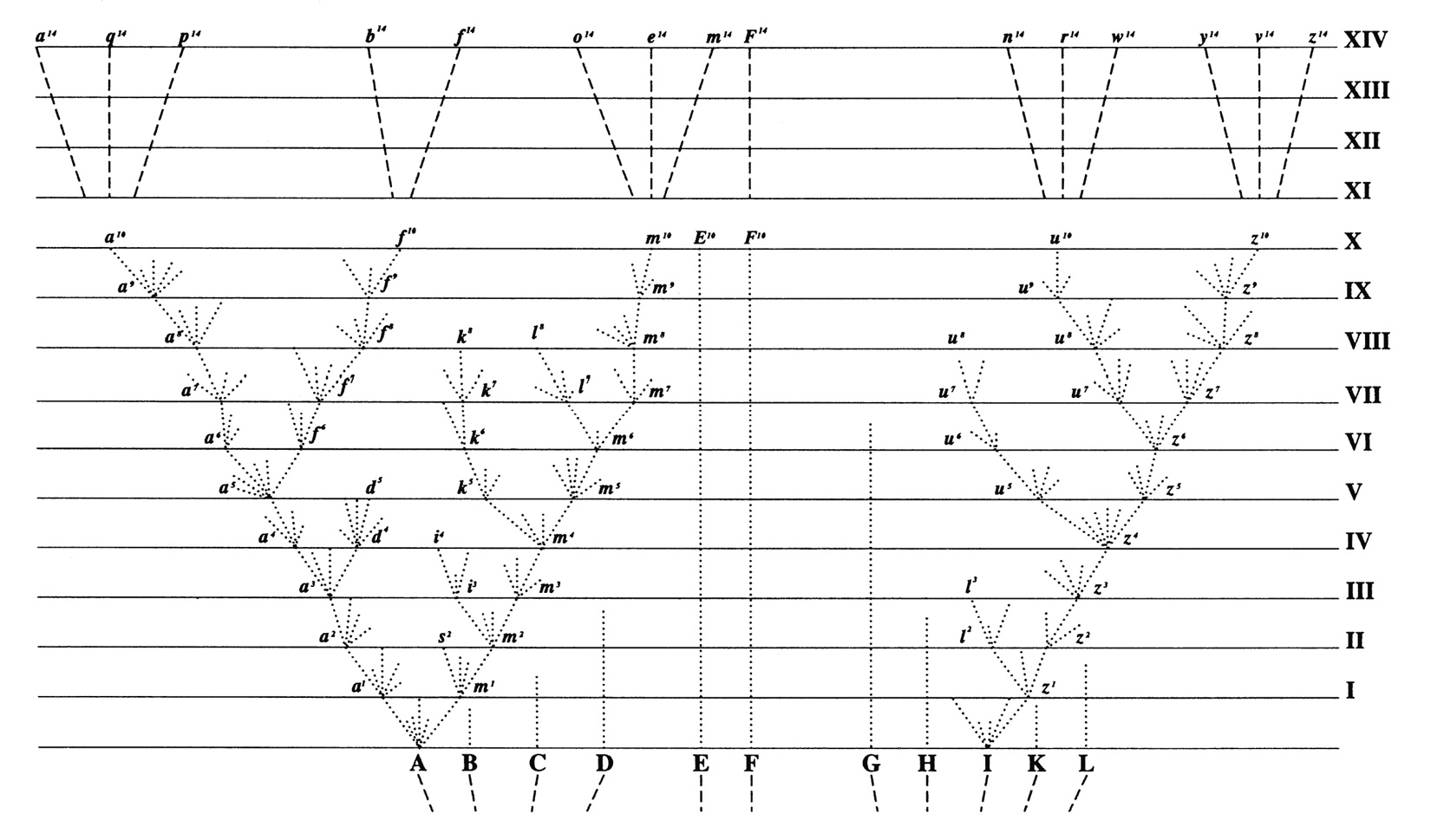

Let (A) be a common, widely-diffused, and varying species, belonging to a genus large in its own country. The little fan of diverging dotted lines of unequal lengths proceeding from (A), may represent its varying offspring. The variations are supposed to be extremely slight, but of the most diversified nature; they are not supposed all to appear simultaneously, but often after long intervals of time; nor are they all supposed to endure for equal periods. Only those variations which are in some way profitable will be preserved or naturally selected. And here the importance of the principle of benefit being derived from divergence of character comes in; for this will generally lead to the most different or divergent variations (represented by the outer dotted lines) being preserved and accumulated by natural selection. … After a thousand generations, species (A) is supposed to have produced two fairly well-marked varieties, namely a1 and m1. These two varieties will generally continue to be exposed to the same conditions which made their parents variable, and the tendency to variability is in itself hereditary, consequently they will tend to vary, and generally to vary in nearly the same manner as their parents varied. Moreover, these two varieties, being only slightly modified forms, will tend to inherit those advantages which made their common parent (A) more numerous than most of the other inhabitants of the same country; they will likewise partake of those more general advantages which made the genus to which the parent-species belonged, a large genus in its own country. And these circumstances we know to be favourable to the production of new varieties. … Some of the varieties, after each thousand generations, producing only a single variety, but in a more and more modified condition, some producing two or three varieties, and some failing to produce any. Thus the varieties or modified descendants, proceeding from the common parent (A), will generally go on increasing in number and diverging in character. In the diagram the process is represented up to the ten-thousandth generation, and under a condensed and simplified form up to the fourteen-thousandth generation. … After fourteen thousand generations, six new species, marked by the letters n14 to z14, are supposed to have been produced.

(Darwin, 1859)

three pairs of diploid annual plant species are related as progenitor and recent derivative. The species pairs are Layia glandulosa and Layia discoidea, Clarkia biloba and Clarkia lingulata, and Stephanomeria exigua ssp. coronaria and Stephanomeria malheurensis. The three cases are examples of Verne Grant’s model of ‘Quantum Speciation’, in which a derived species is budded off and acquires new traits while the parental species continues more or less as before. The derived species differ from their progenitors in different ways and show different modes of reproductive isolation.

(Gottlieb, 2003)

Claim #5: Natural Selection

Can it, then, be thought improbable, seeing that variations useful to man have undoubtedly occurred, that other variations useful in some way to each being in the great and complex battle of life, should sometimes occur in the course of thousands of generations? If such do occur, can we doubt (remembering that many more individuals are born than can possibly survive) that individuals having any advantage, however slight, over others, would have the best chance of surviving and of procreating their kind? On the other hand, we may feel sure that any variation in the least degree injurious would be rigidly destroyed. This preservation of favourable variations and the rejection of injurious variations, I call Natural Selection

(Darwin, 1859)

It may be said that natural selection is daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, every variation, even the slightest; rejecting that which is bad, preserving and adding up all that is good; silently and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at the improvement of each organic being in relation to its organic and inorganic conditions of life.

(Darwin, 1859)

When we see leaf-eating insects green, and bark-feeders mottled-grey; the alpine ptarmigan white in winter, the red-grouse the colour of heather, and the black-grouse that of peaty earth, we must believe that these tints are of service to these birds and insects in preserving them from danger.

(Darwin, 1859)

Case Study Spotlight: How Climate Change is Driving Evolution

Recent studies show that over the recent decades, climate change has led to heritable, genetic changes in populations of animals as diverse as birds, squirrels, and mosquitoes

(Bradshaw, 2006)

The effects of rapid climate warming have penetrated to the level of the gene in a diverse group of organisms. These genetic changes in populations affect the timing of major life history events: when to develop, when to reproduce, when to enter dormancy, and when to migrate

(Bradshaw, 2006)

Geneticists in the 1940s noticed that certain chromosomal inversions in fruit flies (Drosophila) were associated with heat tolerance. These "hot" genotypes were more frequent in southern than in northern populations and increased within a population during each season, as temperatures rose from early spring through late summer. Increases in the frequencies of warm-adapted genotypes have occurred in wild populations of Drosophila ssp in Spain between 1976 and 1991, as well as in the United States between 1946 and 2002. The change in the United States was so great that populations in New York in 2002 were converging on genotype frequencies found in Missouri in 1946.

(Parmesan, 2006)